Lefty, Bob, and the Kid

With Coach Bob McKillop calling the shots and star sophomore Stephen Curry taking them, Davidson’s basketball team is looking to make national waves this season. And Charlotte just might rediscover a long-lost love

Written by Michael Kruse

In the beginning there was Lefty. Charles G. Driesell, who went by Lefty and sounded like grits, came to Davidson College in 1960 to coach the basketball team. What he did in the next nine years was, and is, one of the most amazing, most improbable accomplishments in all of college sports—top ten national rankings for the small school, trips to the national quarterfinals, big, loud crowds in the old Charlotte Coliseum. Before the Panthers, before the Hornets and the Bobcats, before UNC-Charlotte was what UNC-Charlotte is today, Lefty's Wildcats were this town's team.

In the beginning there was Lefty. Charles G. Driesell, who went by Lefty and sounded like grits, came to Davidson College in 1960 to coach the basketball team. What he did in the next nine years was, and is, one of the most amazing, most improbable accomplishments in all of college sports—top ten national rankings for the small school, trips to the national quarterfinals, big, loud crowds in the old Charlotte Coliseum. Before the Panthers, before the Hornets and the Bobcats, before UNC-Charlotte was what UNC-Charlotte is today, Lefty's Wildcats were this town's team.Then Lefty left, in 1969, and went to the University of Maryland, where the pep band played "Hail to the Chief" when he walked into the gym.

Back down in Davidson, the team slipped, first just a little in the early 1970s, then more than that, and by the early 1980s the school's brief, bright blip on the national basketball scene had long since faded to black.

Over those years, and in the years since, Charlotte changed, too. It got bigger, in geography and in population, and with its pro sports teams, its shiny skyline, its creeping reach into the suburbs. Davidson? Even in the mid-1990s, it felt near Charlotte, all the way up in north Mecklenburg County, but it didn't feel like part of Charlotte—too much grass, too much field, too much space, in between, say, exit 18 and exit 30 on Interstate 77.

Now it's almost forty years post-Lefty. Bob McKillop has been Davidson's coach for almost half of those. His team won a school-record twenty-nine games last year, is returning every player of any consequence, is in line for a third straight NCAA tournament appearance, and has on this season's schedule games at Charlotte Bobcats Arena against North Carolina and Duke.

This year could be the year the Wildcats win back Charlotte.

All it took was the legacy of a coach who did his thing and left, the development of a coach who's done his thing and stayed, burgeoning suburbs, and finally a skinny, unafraid nineteen-year-old kid who could end up being the most important player in the history of Davidson basketball.

BUT WAIT. That's getting too far ahead. This is, after all, a story about Davidson basketball, and any story about that has to start on the afternoon of April 18, 1960, when athletic director Tom Couch stood up at a Wildcat Club meeting and introduced the school's new basketball coach to the fifteen supporters who cared enough to come.

Lefty Driesell was twenty-eight and balding. He had won a state championship at Newport News High School in Virginia. His first-year contract at Davidson was for $6,000.

Lefty Driesell was twenty-eight and balding. He had won a state championship at Newport News High School in Virginia. His first-year contract at Davidson was for $6,000."We don't have anything to sell but education," he told the people there that day. "There must be eight or ten good basketball players out there who can get in here. And we're going to find them."

Understand something right now: Davidson does something it shouldn't do when it plays Division I sports. It is a 1,700-student liberal arts school for bookish, serious-minded students, and it has produced doctors, lawyers, pastors, CEOs, and twenty-three Rhodes Scholars. But back in 1960, it was a 900-student, all-male campus, with thrice-weekly chapel and compulsory Sunday evening vespers, a dry campus in a dry county in the middle of nowhere.

The year before Lefty arrived, the basketball team won five games and lost nineteen. None of those wins had come in the Southern Conference. It was, by almost any measure, one of the last places anybody was going to build anything close to a basketball power.

But Lefty was a seller. He sold encyclopedias as a high school coach. He sold the dream of big-time basketball to Davidson prospects and the reality of the education to their mamas. Then he sold Davidson to Charlotte.

But Lefty was a seller. He sold encyclopedias as a high school coach. He sold the dream of big-time basketball to Davidson prospects and the reality of the education to their mamas. Then he sold Davidson to Charlotte.He stomped his feet and flailed his arms and slammed doors and kicked volleyball stanchions in locker rooms and called newspaper reporters and talked to them all folksy and nice. He did something that good Presbyterians don't usually do. He evangelized. He sought and got attention.

In his first game as coach, in December 1960, in tiny, brick-walled Johnston Gym, Lefty's Wildcats beat Wake Forest. Billy Packer, now a CBS commentator, played point guard for Wake, and he was so humiliated he went back to Winston-Salem and stayed in his room for the next day and a half.

Before long, the Wildcats were playing in the old Charlotte Coliseum, which is now Cricket Arena, capacity 11,666. There were, at that time, no major pro sports on the East Coast between Washington, D.C., and Atlanta, and the Carolinas' major college teams were in other places, like Raleigh, Durham, Chapel Hill, Winston-Salem, Columbia, and Clemson. The Wildcats' first game in the Coliseum was on December 18, 1962, and the opponent was Duke, and Duke was ranked second in the country, and Duke was the team that lost.

Before long, the Wildcats were playing in the old Charlotte Coliseum, which is now Cricket Arena, capacity 11,666. There were, at that time, no major pro sports on the East Coast between Washington, D.C., and Atlanta, and the Carolinas' major college teams were in other places, like Raleigh, Durham, Chapel Hill, Winston-Salem, Columbia, and Clemson. The Wildcats' first game in the Coliseum was on December 18, 1962, and the opponent was Duke, and Duke was ranked second in the country, and Duke was the team that lost.Charlotte had its team. That didn't change for the rest of the decade.

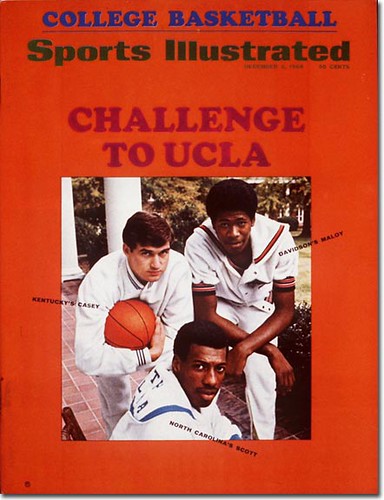

Sports Illustrated ranked Davidson No. 1 in the nation going into the 1964 season. Lefty's teams, in his nine years, beat the teams from Ohio State, Virginia, West Virginia, Alabama, Mississippi State, Pittsburgh, Temple, Memphis, St. John's, Villanova, South Carolina, Maryland, Michigan, and Texas. One team Davidson never beat, though, was North Carolina, and both those losses came in regional finals of the NCAA tournament, by a combined six points, to end the season in 1968 and again in 1969.

Then Lefty left, and that was that. But what happened at Davidson in the 1960s, of course, happened at a different time in a very different Charlotte.

Some dates to consider here:

*Man-made Lake Norman was built in 1963.

*UNC-Charlotte was created by the state General Assembly in 1965.

*Davidson, meanwhile, went coed in 1972.

*Interstate 77 from Winston-Salem to Charlotte was finished in 1977. That meant old Highway 21 was no longer the main way to get from Charlotte up to Davidson.

*The NBA's Hornets played their first game at the second Charlotte Coliseum in 1988. *The NFL's Panthers played their first game in 1995.

Here, then, is the key: All of these dates say something about how Charlotte has changed. The city's population in 1969, when Lefty left, was 240,000. It was 540,000 in 2000, and has gone up by another 100,000 just since then. This isn't just about Charlotte, either, because the transformation of the city made it grow out and up, up I-77, up to the Lake Norman area with all that red-clay shoreline, new roads, new Harris Teeters, new movieplexes, new Starbuckses, fancy roundabouts off Exit 30, hotels, offices, condos to come.

Huntersville, Cornelius, Davidson—they're all doubling in population lickety-split, Huntersville up to 40,000, Cornelius up to 20,000, Davidson up past 10,000. North Mecklenburg High School's student body by now is almost twice the size of Davidson's. The Charlotte Observer opened a Lake Norman bureau two years ago. The volunteer fire department in the town of Davidson has had its calls go up more than threefold in just the last ten years.

All that grass between Exits 18 and 30, all those fields, all that space? There's not so much of it anymore. A gap is being bridged.

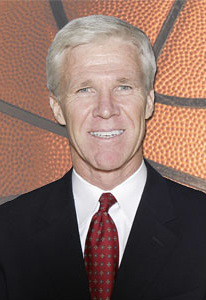

ENTER BOB MCKILLOP. He fits Davidson. Better, truth be told, than Lefty ever did, what with his wire-rim glasses, and his fine suits, and that power dimple tied into his tie. The man won twenty-nine games last year, which is four more than he won in his first three years combined, which at this point seems like a very long time ago.

He is going into his nineteenth season here, and all three of his children have gone here or are going here, and he lives across the street from campus and walks to and from Belk Arena for every game. All of this was never supposed to happen, really, because when he came to Davidson in 1989 from coaching high school at Long Island Lutheran in Brookville, New York, he came mainly to win his way to somewhere else.

He is going into his nineteenth season here, and all three of his children have gone here or are going here, and he lives across the street from campus and walks to and from Belk Arena for every game. All of this was never supposed to happen, really, because when he came to Davidson in 1989 from coaching high school at Long Island Lutheran in Brookville, New York, he came mainly to win his way to somewhere else.Folks forget that. McKillop does not. Quiet bus rides after losses in places like Buies Creek, North Carolina, and Anderson, South Carolina, can humble a man, and did.

"I was brought to my knees," McKillop said one evening this fall out on his back porch.

But his 1993-'94 team went 22-8 and got to the National Invitation Tournament. His 1995-'96 team went 25-5 and undefeated in the Southern Conference. Another NIT.

His 1997-'98 team made it to the NCAAs. His 2001-'02 team got back and lost close to Ohio State. His 2004-'05 team went 16-0 in the Southern and won two games in the NIT. His teams from the last two years: NCAAs again, losses again, close again. Close, close, closer.

Davidson has seventeen basketball alums playing pro ball in Europe. McKillop's teams have grown, and so has he—he delegates more to his staff, he gives more freedom to his players, he's made his playbook more simple. Davidson basketball is a program now.

Last year, something changed. Some sort of tipping point.

Used to be, at basketball games, says Will Bryan, the sports editor of The Davidsonian, the school newspaper, "you picked up a ticket, you went and found your friends, you sat with your friends." No big deal. Not anymore.

After last season, the school sent out season ticket information in July, not August or September. "We realized, ‘There can't be an off-season this year,' " says Martin McCann, the athletic department's marketing man.

After last season, the school sent out season ticket information in July, not August or September. "We realized, ‘There can't be an off-season this year,' " says Martin McCann, the athletic department's marketing man.The lower bowl of red seats in Belk Arena is sold out. Just fifteen red seats opened up over the summer, and those people either moved or died. The premium bleacher seats with the backs: sold out. The family pack season tickets: sold out. The ticket office is now selling season tickets in the regular bleachers, which has never happened.

"You go through our database, and there are a lot of Charlotte addresses," says Jamie Hendricks, the director of the ticket office. "We're getting into territory where we've never been before, or not for a long, long time."

ESPN.com ranks the Wildcats No. 24 going into the season. Lindy's preseason magazine has the team at No. 18. USA Today's Sports Weekly is predicting a trip to the Sweet 16.

The school has a new athletics Web site, www.davidsonwildcats.com . The arena has a new scoreboard. The media guide is fatter.

The school has a new athletics Web site, www.davidsonwildcats.com . The arena has a new scoreboard. The media guide is fatter.Jason Richards is a nominee for the award for the nation's top point guard. Stephen (pronounced STEFF-en) Curry, the star sophomore, is the favorite to win the Southern Conference player of the year. The Sporting News is calling him the third-best shooting guard in America. He's one of fifty players nominated for the John R. Wooden Award—college basketball's Heisman.

Only four schools had their first official practice of this season televised by the ESPNU network. Davidson was one of them.

And one morning earlier this fall, students claimed almost 1,200 tickets for the North Carolina game and the Duke game, both to be played in Charlotte Bobcats Arena. Take away the students who are studying abroad, and there are only about 1,450 students on campus, and many of them spent the night outside the ticket office with beach chairs, blankets, sleeping bags, and tents.

The strangest thing, too, has been happening to Davidson basketball players over the last six or so months. They're getting noticed at the Birkdale Village shopping area in Huntersville and at Northlake Mall in Charlotte. Last spring, Curry and three teammates were on an Easter break road trip, and they stopped at an Arby's somewhere in South Carolina. Five high school kids walked up and wanted to get their picture taken with them.

The strangest thing, too, has been happening to Davidson basketball players over the last six or so months. They're getting noticed at the Birkdale Village shopping area in Huntersville and at Northlake Mall in Charlotte. Last spring, Curry and three teammates were on an Easter break road trip, and they stopped at an Arby's somewhere in South Carolina. Five high school kids walked up and wanted to get their picture taken with them.Then, earlier this fall, someone started a thread on the busy message board at davidsoncats.com. It was titled "Re-Taking Charlotte."

SO. STEPHEN CURRY. Last year, the kid who's no more than six-foot-two and no bigger than 190 pounds led the Southern Conference in scoring, dropped 32 points on Michigan in his second college game, 29 in the league championship game, and 30 against Maryland in the NCAAs, and broke the all-time national record for three-pointers made by a freshman. Then he went and made the under-nineteen national team over the summer.

SO. STEPHEN CURRY. Last year, the kid who's no more than six-foot-two and no bigger than 190 pounds led the Southern Conference in scoring, dropped 32 points on Michigan in his second college game, 29 in the league championship game, and 30 against Maryland in the NCAAs, and broke the all-time national record for three-pointers made by a freshman. Then he went and made the under-nineteen national team over the summer.All of this is only the beginning of his potential long-term importance for the Davidson basketball program.

Remember all that space? Stephen Curry can be a sweet-shooting, baby-faced bridger of that gap. Remember all those dates? About Charlotte growing? Here are two more:

On March 14, 1988, Stephen Curry was born in Akron, Ohio, and he was born there because his father, Dell Curry, was playing for the Cleveland Cavaliers.

Three months and nine days later, the NBA had an expansion draft, and one of the two new teams picking that day was the Charlotte Hornets. The Hornets picked Dell Curry. Dell Curry was the very first Hornet.

He was a good player, one of the best shooters in the league, and ended up playing ten of his sixteen seasons in Charlotte. When he retired, he made the city his home, and started the charitable Dell Curry Foundation. He does community relations for the Bobcats. He is part of Charlotte.

So Stephen Curry grew up here. He was an all-state basketball player at Charlotte Christian and graduated as the school's all-time leading scorer. He was small, though, so the big Atlantic Coast Conference schools weren't interested, which is how in the fall of 2005 he committed to Davidson.

So Stephen Curry grew up here. He was an all-state basketball player at Charlotte Christian and graduated as the school's all-time leading scorer. He was small, though, so the big Atlantic Coast Conference schools weren't interested, which is how in the fall of 2005 he committed to Davidson.Around campus, important people like the athletic director and the new president like to talk about how he's such a good kid, and how he's part of the "fabric," and that's nice.

The Davidson coaches use different words when they talk about him. McKillop: "vision," "balance," "gifted." Matt Matheny, the longtime associate head coach, uses two more:

"Fearless."

"Jugular."

The skinny kid is stronger than he looks. He's cool on the court. He doesn't get riled up and he doesn't get awestruck. He grew up around the NBA. Duke and North Carolina don't scare him.

He also, say the coaches, has some inner assassin. He hunts the big shot, and the big stage, and he has that unteachable something that allows him to miss a shot, two, three…but the next one? It's going in. Last year, in the NCAA tournament game against Maryland, his deep, parabolic three-pointer near the end of the first half went over a seven-foot defender and had Terrapins coach Gary Williams up off the bench cussing and contorting.

"When it's game time, it's game time," Curry says. "I know when to get serious."

"When it's game time, it's game time," Curry says. "I know when to get serious."He is the kid who can keep the Lake Norman newcomers coming to Belk Arena, and people in Charlotte, too. He is, ultimately, the face of McKillop's rallying cry going into this huge season: "Embrace the bullseye," the coach has said over and over.

What he is, for Davidson, at Davidson, is the son of arguably the most beloved basketball player in the history of the city of Charlotte. What that means, according to Jim Murphy, the athletic director, is this: "Everybody that liked Dell now likes Steph. Which is a lot of people." Which gets back to the premise at the start of this story. Stephen Curry could be the Davidson basketball program's most important player ever.

"It's not out of the question," Murphy says

"I would say," McKillop says, "he's sort of the post-Lefty poster boy."

Ron Green Sr. was a sports columnist for The Observer for a long time. He once wrote this: "If you could capture the magic of the Hornets' early years in Charlotte in a painting, it might be the graceful arc of a Dell Curry jump shot."

That arc now goes up I-77, up to north Meck, up to Exit 30, where this fall little Davidson is heading into its biggest basketball season in nearly forty years. Davidson's reach is moving south, Charlotte's reach is moving north, and this could be the year they meet somewhere in the middle.

Shake hands and say, hey there.

How you been?

Long time no see.

1 comment:

dessicant air dryerpediatric asthmaasthma specialistasthma children specialistcarpet cleaning dallas txcarpet cleaners dallascarpet cleaning dallasvero beach vacationvero beach vacationsbeach vacation homes veroms beach vacationsms beach vacationms beach condosmaui beach vacationmaui beach vacationsmaui beach clubbeach vacationsyour beach vacationscheap beach vacationsbob hairstylebob haircutsbob layeredpob hairstylebobbedclassic bobCare for Curly HairTips for Curly Haircurly hair12r 22.5 best pricetires truck bustires 12r 22.5washington new housenew house houstonnew house san antonionew house ventura

Post a Comment